Cover cropping is becoming a foundational strategy in regenerative and sustainable farming. Among these, living cover crops (or living mulches) stand out because they remain active in the soil while the main crop is growing—delivering continuous benefits to soil biology, structure, and fertility throughout the the season. In this article, we explore “Living Cover Crops: The Top 15 Species That Revolutionize Soil Biology”, examine their mechanisms, and discuss how to deploy them effectively for improved soil health, soil microbial communities, soil organic matter, and more.

Introduction to Cover Crops & Living Cover Crops

Cover crops are plants that are grown during periods when the land would otherwise be fallow (e.g. between cash crops) to protect and build soil health. Traditional cover crops are terminated (mowed, tilled, or chemically killed) before the next cash crop cycle. Their residues act as “green manure,” contributing organic matter, nutrients, and soil cover.

A subset of this is living cover crops (or “living mulch” systems) where the cover remains alive beneath or beside the main crop for an extended period, often throughout much of the growing season. These systems allow continuous root activity, which further supports microbial life, nutrient cycling, weed suppression, and soil structure improvement. (Wikipedia)

However, living cover crops bring additional challenges—competition for water, nutrients, or light with the main crop. The balance is delicate, but when well-managed, the gains in long-term soil vitality can be substantial.

Before delving into species, let’s review why they matter.

Why Use Living Cover Crops? Key Benefits for Soil Biology & Health

Living cover crops offer many of the same benefits as conventional cover crops—but with extended advantage:

1. Enhanced Soil Microbial Abundance, Activity & Diversity

A meta-analysis found that cover cropping (in general) increased microbial abundance by ~27 %, microbial activity by ~22 %, and microbial diversity by ~2.5 % relative to fallow control systems. (ScienceDirect) By maintaining live roots in the soil for a longer period, living covers further sustain microbial exudation, rhizosphere interactions, and continuous carbon inputs.

2. Improved Soil Structure, Aggregation & Porosity

Roots of living covers stimulate earthworms, fungi, and microbial glues (such as glomalin) that bind soil particles. This improves soil aggregate stability, porosity, and aeration—helping water infiltration and reducing compaction stress. (SARE)

3. Continuous Nutrient Cycling & Nitrogen Fixation

Leguminous living covers fix atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into plant-available forms, feeding both the cover and (eventually) the cash crop. Meanwhile, root exudates and turnover feed soil organisms and accelerate the mineralization of existing nutrients. (PMC)

4. Suppression of Erosion, Weeds & Soil Temperature Extremes

Living covers continue to shield the soil surface from raindrop impact, reduce runoff, heat load, and serve as a competitive barrier against weeds. (SARE)

5. Carbon Sequestration & Soil Organic Matter Gains

By maintaining living roots and adding biomass over a longer window, living covers can more effectively build soil organic carbon (SOC). Root exudation helps microbes convert organic inputs into stabilized carbon pools. (arXiv)

6. Resilience & Long-Term Soil Investment

Over decades, diversified and biologically rich cover crop systems show stronger gains in biodiversity, ecosystem services, soil quality, and profitability. (arXiv)

In sum: living cover crops can serve as a biologically active bridge between main crops—keeping the soil alive, dynamic, and regenerating.

Choosing the Right Species: Criteria & Trade-offs

Selecting species for living cover systems is more complex than for fallow cover cropping. Some guiding principles:

-

Complementarity with the cash crop: low competition for light, water, nutrients.

-

Root depth & architecture: deeper roots to reach nutrients from lower layers, while not uprooting or interfering with cropping operations.

-

Growth habit: creeping, trailing, or mat-forming species often blend better under or between rows.

-

Nitrogen fixation potential (for legumes).

-

Seasonal dynamics: whether they are evergreen, semi-perennial, or seasonal.

-

Termination option: ease of suppression when needed.

-

Compatibility with tillage / no-till / mechanization.

A classic warning: avoid cover crop species from the same family as your cash crop to reduce pathogen carryover risk. For instance, brassica covers may carry risk for brassica cash crops. (extension.umn.edu)

Below, we propose 15 species (or genera / functional groups) often used or promising as living covers, especially in regions where continuous root systems help soil biology flourish.

Top 15 Living Cover Crop Species That Revolutionize Soil Biology

Below is a table summarizing each species, traits, advantages, and caveats, followed by deeper descriptions:

|

# |

Species (Common Name) |

Type / Family |

Key Advantages in Living Cover Systems |

Considerations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

White clover (Trifolium repens) |

Legume |

Low-growing, persistent, good N fixation, good ground cover under tree crops or between rows |

Can compete for moisture; management of mowing / suppression needed |

|

2 |

Red clover (Trifolium pratense) |

Legume |

Deep taproot, good biomass production |

Less tolerant of close mowing; winterkill in cold regions |

|

3 |

Crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) |

Legume |

Fast establishment, good N fixer, roots loosen soil |

May not persist long-term; may host legumes pests |

|

4 |

Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) |

Legume |

High N fixation (up to ~200 lb/acre), winter hardy |

Can become volunteer weed, may interfere with planting operations (Wikipedia) |

|

5 |

Berseem clover (Trifolium alexandrinum) |

Legume |

Rapid growth, good in warm / mild climates |

Less cold tolerance |

|

6 |

Balansa clover (Trifolium michelianum) |

Legume |

Very soft, quick establishment; good in mixtures |

Lower biomass; shade tolerance variable |

|

7 |

Mucuna (Mucuna spp., e.g. Mucuna bracteata) |

Legume / vine |

Vigorous biomass, nitrogen fixation, weed suppression via smothering (Wikipedia) |

Needs warm climates; may dominate if not controlled |

|

8 |

Tropical kudzu / Pueraria / Neustanthus (N. phaseoloides) |

Legume vine |

Deep rooting, prolonged growth, soil structure improvement (Wikipedia) |

Can become aggressive; careful management needed |

|

9 |

Vigna hosei |

Legume |

Good ground cover, tolerates shade, nitrogen fixer (Wikipedia) |

Susceptible to certain fungal diseases; shallow roots |

|

10 |

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) |

Grass |

Dense fibrous roots, stabilizes soil, compatible with many crops |

Does not fix N; needs termination or mowing |

|

11 |

Festulolium / Fescue mixes (Festuca spp., etc.) |

Grass |

Drought tolerant, deep roots, durable under stress |

Competes for moisture; not N-fixing |

|

12 |

Creeping ryegrass / annual rye (Lolium multiflorum) |

Grass |

Rapid establishment, strong rooting |

May need to manage vigor or suppress at planting |

|

13 |

Italian ryegrass (Lolium perenne subsp. multiflorum) |

Grass |

Good biomass, persistence, root exudates |

Potential competition; must be balanced |

|

14 |

Annual rye / cereal rye (Secale cereale) |

Grass |

Deep roots, strong soil anchoring, good residue when terminated |

Tendency to be tall/weedy if not controlled |

|

15 |

Arachis pintoi (Pinto peanut) |

Legume |

Low-growing, perennial groundcover, good nodulation, soil cover |

Slow establishment; best in warm zones; may not be very frost tolerant |

Below are deeper profiles, use cases, and insights for many of these.

1. White clover (Trifolium repens)

This is one of the most widely used living-cover legumes. Its creeping habit allows it to spread beneath or between rows without overly competing above-ground. It forms nodules to fix nitrogen and persists across seasons if managed well. In orchards, vineyards, or agroforestry, white clover is often used as a living understory. The balance is managing its growth so it doesn’t outcompete main crops for moisture.

2. Red clover (Trifolium pratense)

Red clover has a stronger taproot and may access deeper resources. In living systems, it can contribute more biomass and deeper soil influence. However, it is less tolerant to close mowing and might require occasional suppression.

3. Crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum)

Often used in rotations, but in milder climates it can persist for a time as living cover. It establishes quickly and enriches the soil with nitrogen. It is often used in mixtures to bring diversity and early root growth.

4. Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa)

Hairy vetch is a classic in many cover systems. It is winter hardy, fixes substantial nitrogen, and has been widely adopted. In living cover systems, vetch can maintain vegetative growth and feed soil microbes. It does have risk of lingering volunteers and may complicate planting operations. (Wikipedia)

5. Berseem clover (Trifolium alexandrinum)

Ideal in warmer or semi-arid zones where winter cold is less of a constraint. It establishes rapidly, grows vigorously, and fixes nitrogen. In temperate zones, it may not overwinter well, but in tropical to subtropical zones it can persist.

6. Balansa clover (Trifolium michelianum)

Balansa clover is valuable for its fast emergence and soft growth, making it suitable for mixes or low-competition zones. It can help cover bare patches and provide N input. Its persistence is moderate compared to more aggressive species.

7. Mucuna (Mucuna spp., e.g., Mucuna bracteata)

Particularly in tropical settings, Mucuna bracteata is known for very fast growth, dense canopy, and strong nitrogen-fixing capability. It can suppress weeds via smothering, contribute biomass, and help maintain living cover in warmer climates. (Wikipedia)

8. Tropical kudzu / Neustanthus phaseoloides

Also called tropical kudzu, this species is often used in plantation settings (rubber, oil palm, coconut) as a living cover. Its deep, climbing habit and persistent growth help structure soil and maintain rooting cover. However, in some settings it may become aggressive. (Wikipedia)

9. Vigna hosei

This creeping legume tolerates shade and forms dense mats that protect soil and suppress weeds. It is often used around perennial crops. However, it has shallower roots and may be vulnerable to fungal diseases in some settings. (Wikipedia)

10. Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne)

Though not a legume, perennial ryegrass is excellent for its fine, fibrous root system. It stabilizes soil, enhances soil aggregation, and supports microbial exudation. In a mix, it helps maintain structural integrity.

11. Festulolium / fescue mixes

These grasses offer a blend of durability, drought tolerance, and root persistence. They support soil structure without the nitrogen fixation, so they work best in mixed systems where legumes supply N.

12. Creeping ryegrass / annual rye (Lolium multiflorum)

Fast establishment and aggressive rooting make this useful for more ephemeral living cover periods, or between crop rows. It demands regular management to prevent it from impeding cash crops.

13. Italian ryegrass

A versatile grass that produces good biomass, offers soil stabilization, and presents relatively manageable growth. In living cover systems, careful timing is needed to prevent competition.

14. Cereal rye (Secale cereale)

Often used as a traditional cover, in the context of living cover it can act across seasons in mild climates. It anchors soil, improves aggregate stability, and brings root-based benefits. However, height and biomass control are needed.

15. Pinto peanut (Arachis pintoi)

Pinto peanut is a perennial, low-growing legume used as a groundcover in tropical and subtropical systems. It has good nodulation, decent biomass, and provides living cover without much vertical competition. Its downside is slow establishment and limited cold tolerance.

How to Use Living Cover Crops in Practice: Strategies & Case Studies

Intercropping / Undersowing

In many systems, cover species are sown either ahead of or at the same time as the main crop, or shortly thereafter. They grow alongside without severely shading or competing, especially when carefully selected species are used.

Strip or Inter-Row Planting

Instead of a full interplanting, one may seed living covers in alternate strips or inter-rows, allowing the main crop to dominate in mid-row zones. The cover then “creeps in” to provide soil benefit but with less direct competition.

Periodic suppression

To reduce competition at key crop stages (e.g., flowering, fruit set), partial mowing or targeted suppression of the living cover may be necessary. But suppression does not necessarily kill; it just controls vigor.

Case Example: Vineyards & Orchards

In Mediterranean climates, farmers have used white clover or low-growing legumes as permanent cover between vine rows. The vines get year-round protection from erosion and living root support for soil microbes, while clover’s nitrogen contributes modest fertility.

Case Example: Tropical Plantations

In tropical rubber or oil palm, species like Neustanthus phaseoloides or Mucuna bracteata are often used as living covers. They thrive under canopy shade, maintain soil cover year-round, and assist nutrient cycling. (Wikipedia)

Biomass Target & Soil Gains

Research suggests that > 2 Mg/ha (≈1,780 lb/acre) of biomass is often necessary to reliably increase soil organic matter. (csanr.wsu.edu) In living cover systems, the continuous root presence amplifies that effect.

Long-Term Impact

Long-term cover cropping (including living cover systems) is linked to improved soil chemical, physical, and biological attributes, and better resilience under climate variation. (ScienceDirect)

Management: Planting, Integration & Termination of Living Covers

Planting Timing & Seeding Rates

-

Introduce cover species early enough to allow establishment before heavy crop competition.

-

Use moderate seeding rates to prevent overly dense cover that may strain resources.

-

Ensure good soil–seed contact and moisture for germination.

Nutrient & Water Management

-

Monitor the living cover’s nutrient draw: if it competes for nitrogen, adjust fertilization timing or use more N-fixing species.

-

In water-limited systems, reduce competition by selecting shallow-rooted or low-vigor species.

Partial Suppression

-

Mow or hedge portions of the living cover during key stages of the main crop.

-

Use crimping, rolling, or selective herbicide in systems where allowed (though this may negate the “living” aspect).

-

In some systems, winterkill or seasonal dormancy naturally suppresses the cover.

Monitoring & Adjustment

-

Regularly sample soil microbial biomass, nutrient levels, and root competition effects.

-

Adjust cover species mix, density, or suppression schedule based on observed crop performance.

Transition & Crop Rotation

When transitioning between cover-crop phases and main crops, ensure compatibility—avoid species that may harbor pests or diseases impacting your next cash crop generation. (extension.umn.edu)

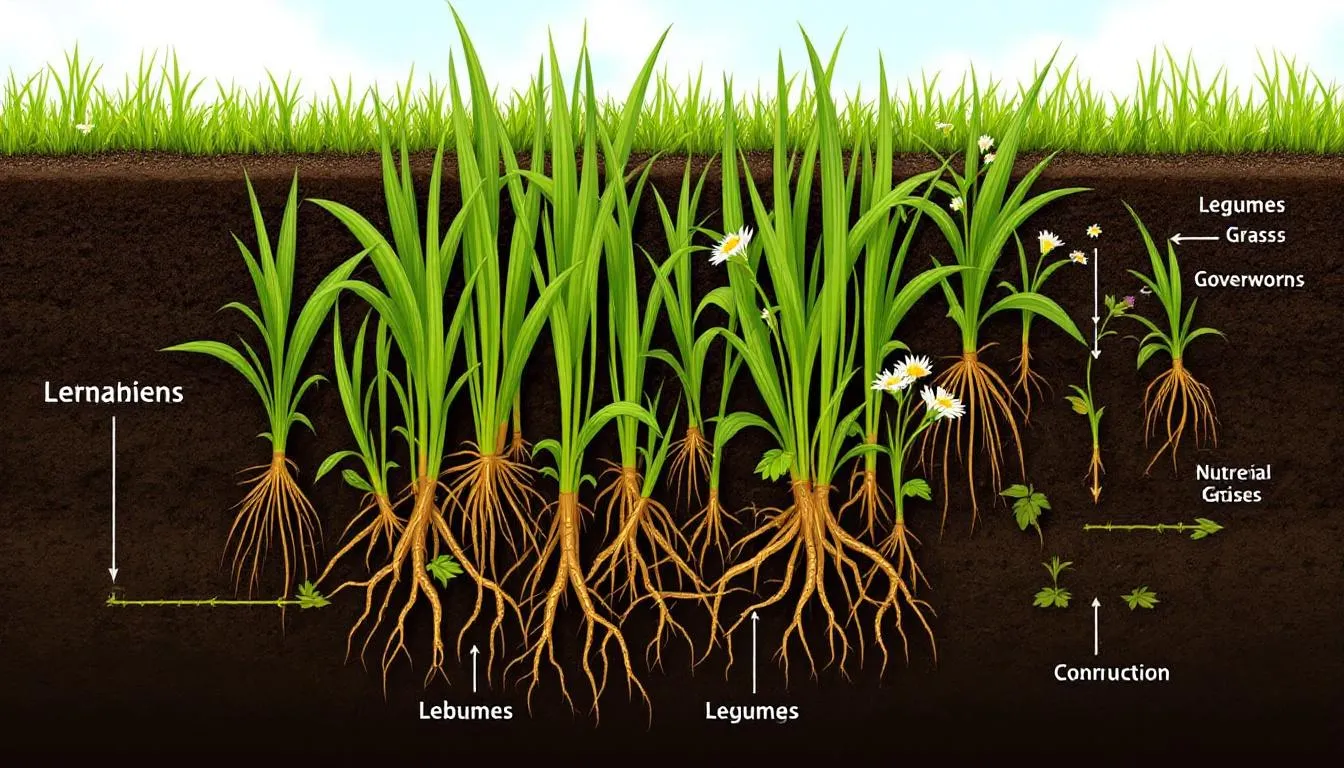

Mixtures & Diversity: Synergistic Effects

A growing body of evidence supports using mixtures of living cover species (e.g., legume + grass + forb) to maximize functional complementarity:

-

Grasses contribute structure and rooting density,

-

Legumes provide nitrogen,

-

Forbs add diversity in root architecture and exudate chemistry.

This diversity helps soil microbial communities thrive across different niches, increases resilience, and enables resource sharing. (SARE)

Challenges, Trade-offs & Considerations

-

Competition risk: Living covers may reduce main crop yields if poorly managed.

-

Water stress: In arid or drought-prone zones, competition for moisture can hamper both crops.

-

Management complexity: Mowing, suppression, and monitoring require active attention.

-

Species balance: Some covers become invasive or overly aggressive if not regulated.

-

Pest / pathogen carryover: Choosing species from safe families is important.

-

Region specificity: A species performing well in one climate may fail in another.

Farmers’ reluctance to adopt, especially in large-scale commodity farming, often stems from yield uncertainty or perceived risk—even though environmental and long-term soil benefits may be compelling. (AP News)

Best Practices for Cover Crop Implementation

Successfully integrating cover crops into your farming or gardening system requires thoughtful planning and ongoing management. To maximize the benefits for soil health, soil microbial communities, and overall productivity, consider these best practices:

Summary & Recommendations

-

Living cover crops provide continuous root activity, keeping the soil biologically dynamic, retaining structure, and cycling nutrients during the crop period.

-

Choice of species is key: combine legumes and grasses or use creeping legumes for low competition.

-

Manage suppression and competition carefully—partial mowing or strip approaches can maintain benefits while protecting the cash crop.

-

Use mixtures for better ecological function and soil microbial diversity.

-

Monitor and adapt—soil sampling, biomass tracking, and yield observations guide refinement.

By integrating well-chosen living cover crop species, farmers can transform their soil into a living, breathing ecosystem—supporting robust microbial communities, increasing organic matter, suppressing erosion, and enhancing long-run fertility. Over time, the “living cover” becomes a cornerstone of resilient and regenerative farming systems.

External references you may find useful:

-

USDA NRCS Cover Crops Overview (pdf) (Natural Resources Conservation Service)

-

“Do Cover Crops Benefit Soil Microbiome? A Meta-Analysis” (ScienceDirect)

-

SARE: “10 Ways Cover Crops Enhance Soil Health” (SARE)